Is the BC Curriculum Reform an Act of Real Reconciliation? An Analysis of Secondary Level Curriculum

Within the past few decades, British Columbia’s secondary education has undergone various revisions that align with political and social changes in Canada. For example, the Canadian government pursued a curriculum change to promote ongoing reconciliation following former Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s 2008 apology to Indian Residential School survivors. In particular, the BC Ministry of Education initiated a curricular reform that emphasizes incorporating “historical wrongs” and “Indigenous histories and perspectives” into various school subjects. However, these two aspects of the new curriculum allow the government to continue to uphold its status quo and settler colonial processes. As author James Miles stated in the Journal of Curriculum Studies, BC’s new “curriculum relies on a vision of multiculturalism that denies and ignores Indigenous sovereignty and simultaneously evades conversations about race and the settler colonial foundations of the Canadian state.” While the BC Ministry of Education has made positive steps to redesign the secondary school curriculum, there is still a significant lack of teaching Indigenous ways of knowing and accurately representing Canada’s oppressive history.

BC’s 2010 Curriculum Change

In 2010, the BC Ministry of Education implemented a new K-12 curriculum to reflect and represent Indigenous peoples and their histories and perspectives. The government issued various alterations to Integrated Resources Packages (IRPs) for each grade level and subject area. The IRP changes to the social studies courses are most significant due to their strong linkage to BC’s and Canada’s history. The government made noteworthy changes in the social studies curriculum to right historical wrongs. For example, scholars Christopher Lamb and Anne Godlewska identified that Indian Residential Schools is now a mandatory component of social studies in grades 5, 9, and 10. In addition, the Truth and Reconciliation Committee was integrated into Social Studies 10, encouraging students to learn about, and become familiar with, the 94 Calls to Action. These mandatory curricula changes illustrate the government’s intention to support reconciliation and Indigenous self-determination.

Another subject area that underwent notable change was English. In 2008, the BC Ministry of Education implemented English First Peoples 12. Two years later, English First Peoples 10 and 11 were developed and integrated. These English courses aim to accurately represent BC Indigenous perspectives and values using a variety of written and oral works. The government does a commendable job of extensively collaborating with local Indigenous nations to develop nine core principles of learning which are later described. These changes to the secondary curriculum highlight the BC government’s good intentions behind enhancing Indigenous representation within the school system. However, unequal power dynamics and colonial relations were still supported through the strategies used to create, design, and implement curricula.

Historically, curriculum development and reform have been undemocratic. Professor Catherine Broom explained that people in positions of power collaborate with individuals who have similar ideas and beliefs “and have shaped the process of curricular reform in order to get the curriculum outcomes they support.” Once a curriculum is created in collaboration with the government and its elected members, the new action plan must be revised. Government officials often provide the revision committees with guidelines to follow. Public citizens are usually unaware of the details of curriculum reform and, therefore, cannot provide feedback or differing points of view. With a lack of public perspective, the curriculum may fail to represent the citizens it is meant to teach. In addition, government officials have the final say regarding what is or is not incorporated into the curriculum, highlighting a power hierarchy that does not challenge biased perspectives or positionalities.

A Critique of the 2010 Curriculum

The Implementation of Indigenous Ways of Knowing

The curriculum revision from 2002 to 2010 brought about significant change. The Shared Learnings: Integrating BC Aboriginal Content K-10 encourages educators to collaborate and consult with local Indigenous communities to “provide students with knowledge of, and opportunities to share experiences with, BC Aboriginal peoples.” This curricular supplement was created by the Aboriginal Education Enhancement branch along with many BC Indigenous nations and educators. This statement of principle for the IRPs recognizes the diversity of Indigenous communities within BC, highlights Indigenous ways of living, and encourages Elders and Indigenous guest speakers in classroom settings. The Shared Learnings resource illustrates an educational shift from homogenizing Indigenous peoples to providing locally defined, meaningful content. The creation of this document underwent a significant shift from talking about Indigenous peoples to researching with Indigenous peoples.

Arguably, the curriculum changes to secondary language arts courses advise educators to incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing into their teaching plans using the First Peoples’ Principles of Learning. One of the statements of principle found in this document describes learning as “holistic, reflexive, reflective, experiential, and relational (focused on connectedness, on reciprocal relationships, and a sense of place).” The First Peoples’ Principles of Learning and the high school English courses were developed by the First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC) and the Ministry of Education. Notably, the developers of this curriculum collaborated with many Elders and community members. One other course that reflects Indigenous statements of principle in the IRPs is BC First Nations 12. Despite this course covering a generalized history of Indigenous nations in BC rather than focusing on local communities, this IRP does a sufficient job of emphasizing Indigenous ways of knowing and learning.

Besides First Peoples-centred social studies and English courses, the revised language arts and social studies curriculum remain silent on Indigenous knowledge integration. For example, social studies courses such as geography, history, and law have little to no coverage of local Indigenous perspectives. The only courses with statements of principle highlighting Indigenous ways of knowing are electives. Lamb and Godlewska explained that integrating Indigenous knowledge systems only in optional courses “centres settler epistemology and ontology in the curriculum.” Relying on teachers to voluntarily integrate Indigenous statements of principles into most language arts classes and relying on students to enroll in First Peoples elective courses undermine the Ministry’s commitment to promoting an understanding of Indigenous peoples among all students. This voluntarist approach works to enhance settler discomfort and ignorance.

A Voluntarist Approach

The secondary level IRPs encourage teachers to facilitate local community participation in structuring classroom education voluntarily. Lamb and Godlewska highlighted, “Such a voluntarist approach assumes the existence of strong community links [between teachers and Indigenous members],…and teachers’ capacity and willingness to undertake work for which they frequently have not been trained.” The Ministry boldly assumes that settler teachers have meaningful connections and relations to local Indigenous communities. Scholars Marc Higgins et al. concluded that settler teachers feel unequipped to teach Indigenous topics due to a lack of resources and pre-existing knowledge.

Higgins et al. highlighted three main factors that often prevent settler teachers from adopting a voluntary, integrative Indigenous teaching approach. The first is a lack of Indigenous education during their university degrees. None of the teachers interviewed in the study received mandatory Indigenous education. This lack of exposure to Indigenous epistemologies evokes emotional responses from teachers tasked with decolonizing BC’s curriculum. Teachers must be adequately educated about local Indigenous perspectives to gain the confidence to teach these concepts to their students.

The second factor contributing to an absence of Indigenous implementation is a lack of personal cultural awareness. Teachers argued that teaching Indigenous cultures would be difficult since they do not understand their own cultural identity. Higgins et al. described this familiar feeling as being a “cultural stranger” to oneself. Whiteness can homogenize white settler persons, limiting distinct ethnicities and ancestries. As a result, many white teachers are left feeling cultureless and thus isolated from conceptualizing the importance of culture.

The third contributor involves the Eurocentric premise on which BC’s curriculum resides. Learning and teaching in a Eurocentric-driven system hinders Indigenous sovereignty and limits opportunities to challenge colonial processes and perspectives. Many teachers commented that whiteness embedded in the education system has influenced their teaching practices and how they acquire information. In addition, Higgins et al. explained that eurocentrism focuses on white teachers and white experiences and is “upheld through false notions of universality, meritocracy, and resistance as a means of leaving white privilege unexamined and unchallenged.” Teachers’ familiarity with white-centred research evokes feelings of inadequacy and uncertainty to challenge BC’s oppressive and exclusionary secondary curriculum.

The Ministry’s Discourse of Multiculturalism

The BC Ministry of Education subtly maintains a Eurocentric education system through a discourse of multiculturalism. Miles found that the term multiculturalism works to uphold the government’s status quo and fails to hold legislative bodies accountable for the assimilative colonial tactics used to create this nation. The multicultural approach to the BC curriculum categorizes Indigenous nations as one of many cultures in Canada’s mosaic, thus denying Indigenous peoples access to their rights, agency, and sovereignty. Further, scholar Verna St. Denis found that creating inaccurate commonalities between immigrants and Indigenous communities erases the latter’s millennia-long connection to the land. As Miles explained, the state’s decision within the curriculum to identify and categorize different cultural groups is founded on the assumption that the Canadian government “has the sole claim to sovereignty and thus is the sole provider of rights and citizenship.” Therefore, the current BC curriculum fails to recognize the very actions of the government that continue to displace, exploit, and oppress Indigenous peoples. The discourse of multiculturalism diminishes the need for curricular implementation of specific Indigenous perspectives and further facilitates the abolishing of Indigenous sovereignty movements.

Suggested Improvements to BC’s Secondary Curriculum

The BC Ministry of Education has made some notable IRPs changes to now include Indigenous perspectives in the curriculum. Through elementary and middle school levels and elective high school courses, Indigenous statements of principle and BC Indigenous ways of knowing are now reflected in some course material. However, there are further steps the government can take to situate BC better on the path toward reconciliation and for our nation to become an active supporter of Indigenous sovereignty.

Firstly, there needs to be a governmental shift away from a voluntarist approach. Indigenous knowledge systems will not be effectively incorporated into classes if teachers are encouraged to collaborate with local Indigenous nations and individually collect and design Indigenous course material voluntarily. When the onus is put on teachers to develop an Indigenous-centred curriculum, they face various structural barriers. Teachers lack Indigenous education and personal cultural identity and teach in a Eurocentric system that centres whiteness. Therefore, it is often uncomfortable, challenging, and time-consuming for teachers to find appropriate resources that challenge this educational system. The Ministry should develop mandatory Indigenous statements of principle in the collective secondary curriculum, as done in elementary and middle levels, so as not to burden teachers with constructing course material. Providing teachers with a mandatory course framework allows them to employ their own agency to shape their class teachings into a localized Indigenous perspective. Further, the Ministry should improve funding to establish more Indigenous educational opportunities for existing BC teachers. A greater understanding of BC Indigenous ways of knowing will grant settler educators the confidence to take on First Peoples implementation strategies.

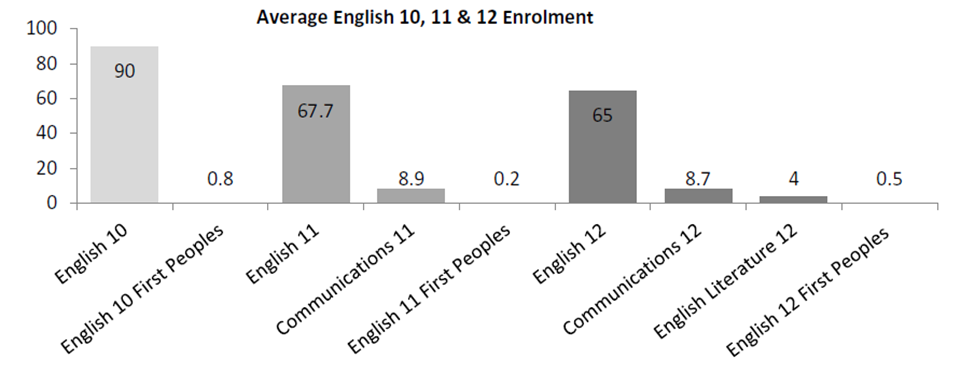

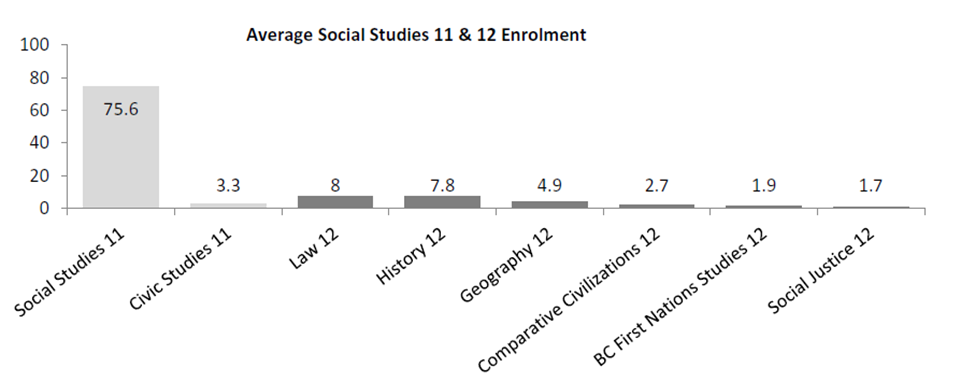

Another aspect of this voluntarist approach is evident through course elective choices for students. For example, while English First Peoples 12 counts towards the English graduation requirement, there is much higher enrolment for the traditional English course. In addition, BC First Nations 12 is considered an upper-level social study elective but has significantly fewer enrolment rates than geography, history, and law. This is problematic as the latter three courses do not have mandatory coverage of Indigenous ways of knowing. The Law 12 IRP has less than three per cent coverage of Indigenous perspectives. One strategy the Ministry has now implemented to encourage students to take First Peoples-oriented courses is a graduation mandate. According to CBC News, starting in the 2023/2024 school year, high school students must complete an Indigenous-focused course to graduate. Hopefully, this increases student enrolment in courses like BC First Nations 12 and English First Peoples 12.

From a more political perspective, James Miles, in another journal titled Historical Justice and History Education, created two manageable ways for educators to teach historical injustices in settler colonial spaces. The first suggestion is that settler colonial nations, such as Canada, must be recognized as settler colonial nations. Historically, the curriculum has protected Canada’s status quo and painted the state as progressive and accepting of all cultures. However, Miles argued that Canadian schools have portrayed Indigenous peoples as separate from the state. This ideology perpetuates a multicultural discourse that renders Canada a political body that has “moved beyond and disposed of its colonial past.” Positioning assimilative, colonial, and oppressive tactics as a thing of the past denies and invalidates the current struggles of Indigenous nations.

The second suggestion encourages sovereignty, rights, and citizenship not to be solely determined and recognized by the colonial state. Miles stated, “Citizenship education and building a sense of national identity remain key goals of history and social studies education. These curricular requirements position the state as the sole provider of citizenship and rights and deny Indigenous peoples their sovereignty. Miles argued that Indigenous nations should be portrayed in the education system as having an equal sovereignty system to Canada. Therefore, the histories of treaties and Indigenous-settler relations must be taught within the curriculum to demonstrate the conditions on which the Canadian state was founded. This implementation will allow students to analyze Canada’s reconciliation discourse and recognize how the state may not respect Indigenous sovereignty. Further, it highlights that Indigenous history cannot be excluded from understanding the creation of Canada’s nationhood and its continued logic.

The Impact of Curriculum Change on Students

Integrating these suggestions into the curriculum will benefit Indigenous and non-Indigenous students alike. Scholar Yatta Kanu in a Manitoba-based study, found that a social studies class that integrated Indigenous ways of knowing into daily classroom lessons increased Indigenous students’ academic success and attendance rates, improved self-confidence, enhanced connection to cultural identity, and encouraged student voice. Implementing Indigenous ways of learning also improved the critical thinking skills of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. One Indigenous learning strategy employed in this study was discussion circles. Talking circles allowed students of various ancestries to challenge Western forms of learning that often devalue Indigenous thoughts and experiences. Further, the talking circles fostered a learning space built on equal partnership, respect, and non-threatening attitudes. Participating in discussions that uplift perspectives and experiences often pushed into the marginalized periphery allows Indigenous youth to feel heard, valued, and well-represented. Shifting BC’s curriculum into one that encourages the sharing of local Indigenous experiences and teachings will foster a safe environment for all students and will allow the youth to grow in a culturally respectful and responsive manner.

Conclusion

In response to Prime Minister Harper’s 2008 apology to Indian Residential School survivors and TRC’s 94 Calls to Action, the BC Ministry of Education has implemented curriculum change to all levels of education. Within the secondary level, a few social studies and English courses have incorporated Indigenous knowledge. However, most of the curriculum lacks statements of principle relating to Indigenous perspectives. In addition, much of the Indigenous implementation is voluntary, putting the onus on teachers, who lack knowledge and resources, to create Indigenous coursework. The Ministry also employs a discourse of multiculturalism that fails to recognize Indigenous nations’ sovereignty and their distinct, historical relationships to the land.

To improve the current curriculum, the BC Ministry of Education should eliminate a voluntarist approach and instead mandate Indigenous statements of principle in course frameworks. Further, Indigenous-oriented high school courses should be required courses. Finally, the Ministry of Education must challenge the representation of the Canadian state and recognize that Indigenous sovereignty is as legitimate as Canadian sovereignty.

More implementation of Indigenous ways of knowing into BC’s curriculum will benefit educators and students alike. Indigenous students can experience greater self-confidence, pride in their culture, and academic success. Indigenous and settler students can strengthen critical thinking skills and their student voice within learning environments. Further, Indigenous education within BC’s curriculum can improve students’ and educators’ understanding of how our society functions and how we relate to one another. Reforming the school curriculum is essential in positioning BC and its residents in a place of sustainable reconciliation and ongoing support for Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.